Source: KTICRadio.com

Two Kansas State University faculty members recently joined experts from around the world in China for an information exchange about micro-irrigation technologies.

Freddie Lamm, research irrigation engineer at K-State’s Northwest Research-Extension Center in Colby, and Gary Clark, senior associate dean for the College of Engineering and professor of biological and agricultural engineering, were invited presenters at the Irrigation in Action Symposium at China Agricultural University in Beijing, in October.

Lamm has been in communication with researchers at China Agricultural University since 2000. In the last 15 years, he has made multiple trips to China to examine irrigation strategies there, while researchers from China have visited Kansas twice to view studies underway that involve Lamm’s research specialty, subsurface drip irrigation (SDI).

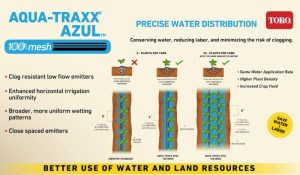

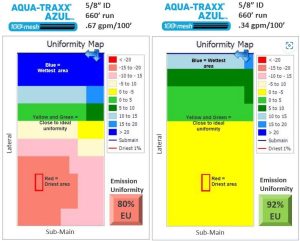

SDI is “top-of-the-line for water use efficiency,” according to Lamm. It is a method of micro-irrigation where drip irrigation lines are installed below the soil surface.

“The reason we would be so interested in SDI in Kansas is that by installing it below the ground, we can get multiple years of usage out of it, thus lowering our investment costs,” Lamm said.

While there are some challenges associated with SDI, including the investment costs, germination concerns in dry years and the potential for rodent damage, he said most Kansas agricultural producers who have adopted SDI have been pleased with it.

Lamm found that Chinese agricultural producers have also witnessed success with SDI. The Inner Mongolia region of northeast China is similar to western Kansas in many ways, he said, although it is a bit colder and has a shorter growing season compared to Kansas.

“China is looking at several types of micro-irrigation for many different row crops and also for greenhouse production,” Lamm said. “The interest in my expertise is for row crop production using SDI.”

In the Inner Mongolia region, the government is seeking to develop more than 1 million acres of SDI for field corn in the next five years, he added. The yields from the corn performance trials there on SDI acres have thus far been respectable.

“They are going to need to make some adaptations, because any type of micro-irrigation requires care and attention to make sure it is properly maintained to prevent clogging,” Lamm said.

Adaptations would come from both Chinese universities and government agencies, as well as from the companies developing the drip irrigation lines being distributed to smallholder farms. Lamm and other international experts involved with the technical exchange were able to visit with Chinese experts, one another, microirrigation company staff and smallholder farmers during the latest trip, which he said created a rewarding and interesting experience for all.

“We had researchers from Texas, Florida, South Dakota, two of us from K-State, a colleague from Spain and a colleague from Israel,” Lamm said. “If the technology doesn’t work exactly the same way in another country or another region of the United States, maybe we could modify it slightly to fit those new conditions.”

On this most recent trip, Lamm said he was pleased to find that an adaptation discussed in Kansas during a Chinese visit in 2014 had been successfully adopted in Inner Mongolia to improve germination using SDI. The concept, though appropriate for Inner Mongolia, would not likely be successful in Kansas due to climatic differences.

Lessons for irrigation in the U.S.

While the experts provided Chinese irrigators with tips on adapting micro-irrigation technologies and improving crop germination, Lamm said he was able to bring tips from them back to the United States.

Lamm and other K-State researchers serve on a U.S. multistate committee that is currently focused on scaling microirrigation technologies to address the global water challenge. As an example, it might mean taking an advanced technology with high inputs and adapting it for low-input agriculture. Also, it can just as easily work in reverse, where a success under low-input agriculture is modified and adopted by more mechanized agriculture.

“For instance, in some parts of the United States, producers might be growing a high-value vegetable or fruit crop, such as strawberries,” Lamm said. “We’re not going to be able to implement that same level of technology or expend that amount of money for our typical crops in Kansas. So, how do we scale the technology for that high-value crop to a lower value crop, such as corn?”

That question, among others, is what the multistate committee is trying to answer and is finding some answers through these international exchanges.

Additionally, Lamm found that producers in China are using narrow rows, 12 inches apart, to produce crops. Seeing that made him want to try it in Kansas, simply to test if narrowing the rows around the drip line would perhaps lead to better germination and better yields. That research is still underway.

The information exchange will continue, with micro-irrigation evaluation trips scheduled between the U.S. and China for at least the next three to four years.