Original article from Western Farm Press (by Todd Fitchette)

California cotton growers and water-starved fields could benefit from a conservation tillage practice not typical to this Golden State cash crop, although the practice is widely implemented and accepted elsewhere in the United States.

California cotton growers and water-starved fields could benefit from a conservation tillage practice not typical to this Golden State cash crop, although the practice is widely implemented and accepted elsewhere in the United States.

At Lucero Farms in Firebaugh, Calif., the decision this spring to implement no-till practices on cotton planted in western Fresno County seems a good one given a 20-percent water allocation via the State Water Project.

“I think it’s a good system for growers,” said Danny Ramos, farm manager with Lucero Farms. The farm entity rotates cotton with processing tomatoes.

Through the help of the University of California and others, Lucero Farms, which farms in the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys, is using no-till conservation practices on 122 of the 223 acres of Phytogen 805 Pima cotton on the Firebaugh farm.

According to Jeffrey Mitchell, UC Cooperative Extension cropping systems specialist based at the Kearney Agricultural Research & Extension Center in Parlier, Calif., this could be the only commercial production of cotton using no till in California.

However, it is not just the water savings which makes no-till conservation tillage methods attractive, according to Mitchell. Farmers can also realize cost saving benefits in labor and equipment. University studies back this up.

A study conducted at the UC West Side Research and Extension Center in Five Points, located southwest of Fresno, reported that the number of tractor passes for a cotton-tomato rotation grown with a cover crop was reduced from 20 passes in the standard treatment to 13 passes with conservation tillage methods.

Fuel use in the study was reduced by 12 gallons. Labor needs were reduced by two hours in the study plots. The result was a cost savings of about $70 per acre.

Defining “No Till”

A UC Davis publication reports that conservation tillage – the larger umbrella term under which the term “no till” conservation is defined – was defined in 1984 by the U.S. Soil Conservation Service (now the Natural Resources Conservation Service).

No till is a tillage system which maintains at least 30 percent of the soil surface covered by residue after planting, primarily where the objective is to reduce water erosion.

According to Mitchell and others, the objective of the residue left behind in the fields is to hold residual moisture and reduce the need for costly irrigation water.

Ramos confirmed this. He told attendees at a University of California-sponsored Cotton Field Day hosted at Lucero Farms about the appreciable decrease in water use on his no-till cotton field, compared to the minimally-tilled cotton planted in an adjacent field.

As of the end of May, Ramos had used four inches of water on the no-till plot and six inches in the minimum-till field.

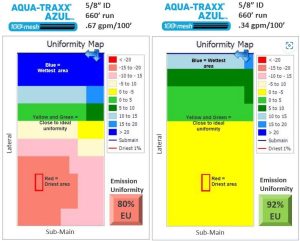

Drip irrigation in Lucero’s cotton fields plays a vital role in controlling water usage, Ramos said. He rotates processing tomatoes and cotton. The drip irrigation has helped boost tomato yields by 20 percent.

Additionally, pests and weeds are less of a factor in the no-till system, according to several speakers at the field day. Ramos suspects the ground cover from the previous crops incorporated into the soil, and the agricultural residue on the surface, reduces weeds germination.

It was also suggested during the field day discussions that the arid environment above the soil surface, due to drip irrigation practices which release water where the plants need it the most, may play a positive role in pest management since pests do not like dry conditions on the soil surface.

Based on a UC Davis report, conservation tillage can reduce the number of times tractors cross farm fields. While this protects the soil from erosion and compaction, Mitchell says the erosion factor alone is just one of the larger, regional issues impacting California agriculture as dust and tractor emissions continue to become targets of state and federal regulators.

In no-till or direct seeding systems, the soil is left undisturbed from harvest to planting except perhaps for the injection of fertilizers, according to UC Davis. Soil disturbance occurs only at planting by coulters or seed disk openers on seeders or drills, and at that, the soil disturbance in planting under these systems is much less than traditional means, Mitchell says.

Drawbacks

Mitchell admits not all is not positive when considering no-till conservation methods when planting cotton. One of the drawbacks is generating a stand from seed.

“Cotton is not as easy to establish by no-till methods,” Mitchell says.

Yet, no-till methods are not new to cotton elsewhere in the U.S. Cotton was one of the first no till crops in Kentucky and Tennessee in the 1950s and 1960s.

The acceptance of no-till conservation practices, says Mitchell, came about in other regions of the country due to the lack of irrigation water and a heavy reliance upon rain for crops.

California agriculture has become a successful multi-billion-dollar industry due to irrigation technologies from ground wells and the establishment of canals systems in the agriculturally rich river valleys of the state.

This is due in part to a changing political climate in California which for a number of years has siphoned off water traditionally provided for agriculture and allowed it to flow out to sea.

Pictures of dead permanent crops and fallowed, arid farm fields in California became fodder for television news features and politically-charged protests which emphasized the need for additional agronomic practices to keep farming viable and profitable in California.

Mitchell and others are trying to educate farmers about no-till practices for the economic benefits while still pointing out the positive environmental benefits.

Mitchell is a founder of Conservation Agriculture Systems Innovation, a diverse group of more than 1,800 farmers, industry representatives, UC and other university faculty, and members of various public and private agencies looking at conservation tillage practices to save input costs for farmers, all while preserving California’s rich farmland.