Original post by National Geographic (Peyton Fleming and Brooke Barton)

California and tomatoes are synonymous. Drive along Interstate 80 near Sacramento these days and you’ll see an endless parade of trucks, each filled to the brim with 26 tons of glistening succulent red tomatoes. It’s so many trucks, one after another, that you begin to understand how California grows 30 percent of the world’s processed tomatoes.

Many of the trucks are headed to Dixon, California, home base of a Campbell Soup processing plant that handles 240 loads of tomatoes every day – 14 million pounds, all of them for use as tomato paste and diced tomatoes that are the foundation ingredient of Prego spaghetti sauce, Pace Salsa, V8 beverages and thousands of other Campbell products.

It’s a mind-boggling operation, especially when you ponder the vast amount of water that’s needed for all this. The processing plant itself uses more than three million gallons a day to move, clean, and cook tomatoes. Out in the fields, growing just one pound of raw tomatoes requires about nine gallons of water. Multiply that times the 20,000 acres that are under production for Campbell and you get the idea.

Add in the fact that hundreds of other crops are also tapping into California’s dwindling water supplies, and you ask yourself, “How do Campbell and its 50 independent growers manage it, and how are they preparing for a likely drier future?’

Last month, Ceres’ water team got some insights during a half-day visit to the 38-year-old processing plant and two nearby farms operated by Dave Viguie and Dustin Timothy, who together grow 1,700 acres of tomatoes.

It was clear from the outset that water is on everyone’s mind 24-7. Water prices, water rights, drip irrigation, and last year’s dry winter are oft-repeated topics in every conversation. All have a common thread – the days of cheap limitless water supplies in California are fast approaching their end, and in districts further south in the Central Valley, are already here.

The folks at Campbell Soup know this. Which is why the company set goals last year to reduce water and fertilizer use by 20 percent per pound of tomatoes by 2020. This is on top of a 50 percent water reduction goal for its manufacturing plants. Meeting these goals falls on Daniel Sonke, who manages the company’s agriculture sustainability programs.

“Dr. Dan,” as he is affectionately referred to by colleagues, is looking under every rock to find savings, beginning with the processing plant and its dizzying array of conveyor belts, evaporators, heat exchangers, and water cooling towers. Water for the plant comes from four groundwater wells that are part of the Putah Creek Watershed.

Water recycling and reuse practices, among other steps, have already reduced the plant’s water footprint from 4 million to 3.6 million gallons a day. “That’s 10 percent in just one year. We feel pretty good about that,” he said.

More improvements are anticipated as the company implements recommendations from a comprehensive audit done by a research team from UC Davis. The audit focused on maximizing water/energy efficiencies, a strategy with big environmental and financial implications, given that 35 percent of the plant’s electricity use is simply for moving water.

But a far bigger footprint is the company’s growers.

Campbell sources its tomatoes from independent family-owned farms, so the company cannot issue water use reductions by edict. But it can help its farmers through engagement and the power of suggestion.

“Let’s focus on some key indicators and let the farmers do the rest,” Sonke said, describing his philosophy.

Sonke is a big believer in talking with his stakeholders. That means spending countless hours meeting with his growers about the company’s objectives and how growers can help – while reaping the benefits, too. Collecting and analyzing key performance data for each of the farmers is also enormously important. “We find that seeing how they benchmark against others gets the wheels turning,” says Sonke.

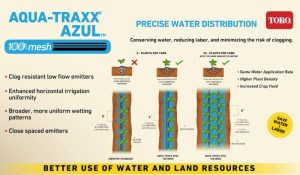

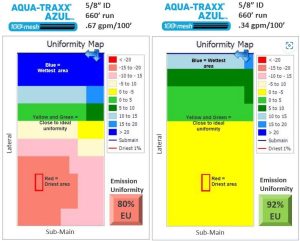

One especially promising strategy is replacing sprinklers or furrow irrigation with drip irrigation. It’s an expensive switch – it costs about $1,000 per acre to install the drip system underground – but the benefits are obvious. In addition to cutting water use by roughly 10 percent, it saves on fertilizer and helps farmers boost their tomato yields.

“We’re seeing energy savings and we’re using less water, but if we didn’t have the higher yields it would be hard to justify,” said Dustin Timothy, 35, who borrowed money to install drip irrigation on 500 acres.

“The driver for the drip is the economics, more tomatoes produced,” David Viguie, a San Francisco transplant who has been growing tomatoes for Campbell for two decades, said matter-of-factly.

Viguie’s bottom-line perspective is hugely important as Sonke and his colleagues push to integrate sustainability more deeply across the company’s value chain.

“Being financially sustainable is just as important as being environmentally sustainable,” said Craig Leathers, a Campbell senior agriculture representative, who works closely with all of the local farmers.

Drip adoption rates in this watershed are still lower than districts further south where water is scarcer and more expensive. Still, Sonke is encouraged by the steady uptake of drip systems; 39 percent of its growers’ acres are now using drip, up from 29 percent a year ago. Next year, he hopes to get to 49 percent.

As for hitting the 20 percent agricultural water reduction goal by 2020, Sonke says he is “cautiously optimistic.” Wider use of drip systems will be a key factor. On the manufacturing side, a key driver is the company’s financial support on processing plant improvements. “The company is allowing us more flexibility to invest in water-savings projects. Sustainability is now allowed to have a longer payback period to achieve ROI (return on investment), which is very important,” he said.

In the end, though, Sonke cannot succeed unless his growers also succeed. Satisfactory profit margins are a prerequisite of growing tomatoes more sustainably.

“There’s a lot of pressure on these guys to go to higher value crops,” Leathers said. “We, as a company, are always worried about losing them. We’ve got to keep these guys profitable.”