Source: Deseret News

With a crop built around a holiday tradition — think pumpkins at Halloween — a farmer sometimes has to break with tradition to make the best use of his fields.

With a crop built around a holiday tradition — think pumpkins at Halloween — a farmer sometimes has to break with tradition to make the best use of his fields.

It’s that time of year when pumpkins are coming out of the fields, into the stores and onto front porches everywhere. But this year, farmer Matt Peterson grew his crop of future jack-o’-lanterns using only one-third of the water his farm has traditionally used.

In this era of widespread drought and water shortages, some say the impressive water savings in Peterson’s Ogden pumpkin patch could be a model for other farmers.

“We grow about 60 acres of pumpkins every year,” Peterson said as he walked through a field of green, littered with the giant orange fruits that are so popular this time of year.

Peterson, whose farm does business under the name Ogden Bay Produce, has water shares in a canal company that allows him to take water for 19 hours every 7 ½ days. In earlier years he’s poured 1,500 gallons per minute into his fields during his watering periods.

“Now,” Peterson said, “I’m pumping 500 gallons a minute and I’m using that to water this entire farm. So that’s one-third of what I’m allotted to use. Same amount of production, same number of acres.”

As he pointed to water gushing over a spillway, he said, “Actually, all this water going over the spillway is considered wastewater to me because my pump’s not using it. So I have an agreement for that to go down and water the neighboring farm.”

So, how did he manage to save two-thirds of his water?

He started by ordering a textbook from Amazon and taught himself the principles of drip irrigation. The old method — flood irrigation — basically just allows water to flood through the field by flowing down the length of the furrows. The water has to soak through the dirt sideways two or three feet to reach the roots of the pumpkin plants.

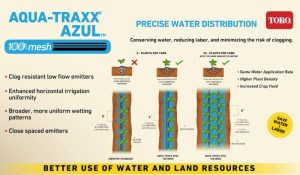

Peterson’s new system has feeder pipes that run alongside the field while dozens of drip-lines branch off into the pumpkin patch. “This drip-line is installed right underneath the plant,” Peterson said, “so it’s inches away from the root zone. It’s putting that water right where it needs to go.”

Tiny holes in the drip-lines are spaced a foot apart and they just barely ooze out the water. “A quarter of a gallon of water per hour,” Peterson said as he rubbed his thumb over water slowly seeping from one of the holes. “That’s all it is, right there.”

He also installed electronic sensors in his fields so he can monitor moisture conditions while he’s seated in his home office. “It’s been a lifesaver because I can come and sit down — that’s my morning routine — to check my water on every field,” Peterson said. “And I do it in the computer.”

The upgrade to “Pumpkin Patch 2.0” cost nearly $10,000, but a federal agency covered the tab. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service paid 100 percent of Peterson’s cost and provided technical assistance to help move him beyond flood irrigation.

“People have grown pumpkins in this area for generations and it’s always been flood,” said Hannah Freeze, a conservation planner for the Natural Resources Conservation Service. “Matt really changed the game to go to a drip system. And people are watching to see if it’s going to be successful.”

There’s another advantage of drip irrigation: Peterson’s pumpkin patch is less subject to the on-and-off watering cycles dictated by his water allotment. “You apply just the water that is needed for that plant just at the time it needs it,” said Craig McKnight, district conservationist for the service.

“There aren’t a lot of people doing this around where I live,” Peterson said. “It’s a new way of doing it, and I think a lot of farmers don’t want to change.”

Part of the reason farmers are reluctant to become more water-efficient is because they fear the “use-it-or-lose-it” provisions of Utah water law. “It’s sad the way that our laws are written in that we’d have to give up that water,” Peterson said. “I know that discourages a lot of farmers around here from doing it because they don’t want to lose that allotment.”

Peterson managed to work out a friendly deal to send his saved water to his neighbors. It’s apparently a win-win for all concerned.

The federal Natural Resources Conservation Service doesn’t always pay 100 percent of the cost. But the agency does have generous cost-sharing formulas. They offer not only technical assistance but help with the paperwork.

“You know, water is on everybody’s mind,” Freeze said. “And so I think the more efficient that we can be, the better off that we can be as producers and farmers.”

Article by John Hollenhorst via Deseret News